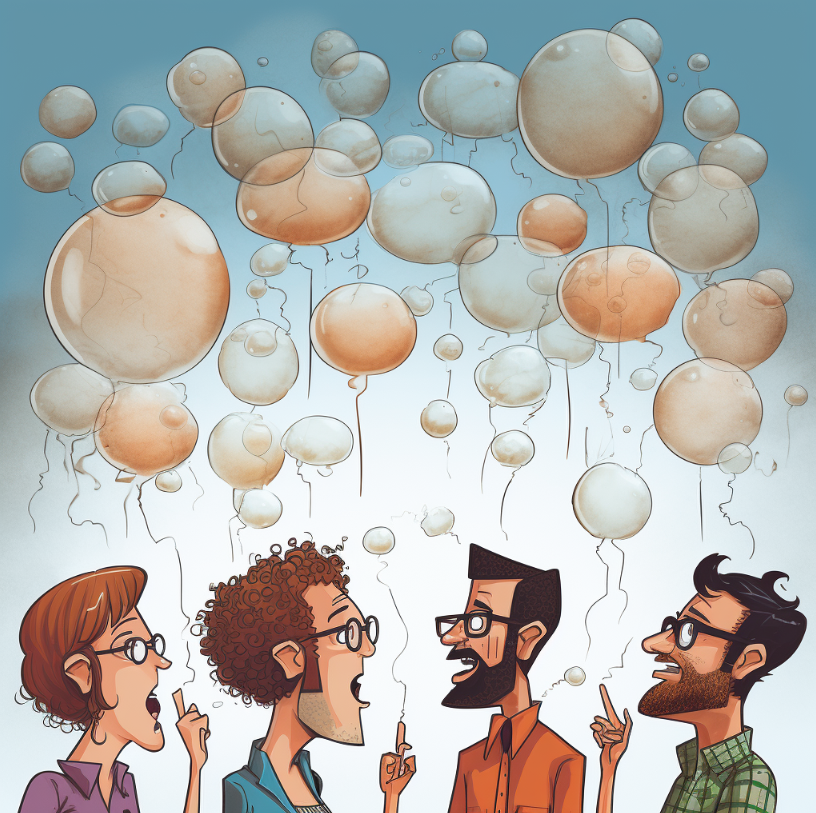

Cold: Your memory of an event may be disproportionately affected by two things

Continuing my series on the thoughts of Daniel Kahneman brings us to the Peak-End rule, which is an odd one.

The way you remember an event is heavily weighted by the most intense point in the experience – or the peak – and also by the end of the experience.

This can lead to some odd applications. In two groups of patients getting a colonoscopy, Group A was given the standard procedure. Group B had a few extra minutes where the scope was in a more comfortable position. The people in Group B rated the procedure as less painful, which raises some interesting ethical questions. Is it right for a doctor to prolong a procedure so the patient has a better memory of it?

How can we apply the peak-end rule to events?

First, focus on creating a memorable peak moment. Identify and amplify the most exciting part of the event. This could be a keynote speech, a performance, … who knows. Try to surprise and delight – maybe with a surprise guest appearance, or special gifts.

Note however that the peak-end rule applies to how people remember the event. It doesn’t necessarily incentivize them to attend the event. Those are two different things. In an article I link below, Ken Holsinger points out that what people attend at an event, or what they remember, is not what influences them to come.

Second, end on an engaging, positive, enjoyable high note, and make sure you have your logistics right so the departure process is pleasant. What I hated the most about church when I was a kid was that after suffering through the whole service you had to wait in line to get out. That was torture.

One good way to end a business event is to have networking with high-quality refreshments and opportunities for meaningful connections.

Just because you should focus on the peak and the end doesn’t mean you should neglect other experiences. If registration and lunch are a mess, people will remember that.

The planning fallacy is also relevant to events. Kahneman and his collaborator Tversky found that humans underestimate the amount of time and the required resources to complete a project. This leads to overly optimistic timelines and budgets.

Here are some things you can do to avoid that.

- Look at historical data from similar projects

- Break down tasks into smaller, manageable tasks that are easier to estimate

- Establish clear milestones and checkpoints

- Include buffer time for unexpected delays

- Build in flexibility up front

- Ask experienced people to review your plan

- Use a pilot project to scope out things you’re not sure about

- Use project management tools, including visualization tools

Links

Ken Holsinger’s insights on what people really want with events