In this 4-part series I’m going to give some perspective on how the publishing industry got into its current mess with overreliance on Google and competition from artificial intelligence. If you’d rather watch and listen than read, click on the “Video” links immediately below.

Part 1 will provide some background information about copyright. Video

Part 2 discusses the search bargain – why publishers allowed tech giants to crawl and index their content. Video

Part 3 addresses how generative AI has changed the equation. Video

Part 4 predicts what comes next and suggests some actions to take. Video

Part 1 – Copyright

As I’ll discuss in more depth later, Google is a copyright anarchist. They take other people’s work and do what they please with it. This is partly a matter of business operations and partly a result of their mission statement.

Technology disrupts copyright

To some extent you can think of copyright as “the right to copy.” As publishing technology got better, it became easier and easier to make reproductions. Before the dawn of modern copyright with The Statute of Anne in the early 18th century, these issues were controlled by royal charter or privileges granted to specific printers or publishers. The Statute of Anne vested that right in the author.

To some extent you can think of copyright as “the right to copy.” As publishing technology got better, it became easier and easier to make reproductions. Before the dawn of modern copyright with The Statute of Anne in the early 18th century, these issues were controlled by royal charter or privileges granted to specific printers or publishers. The Statute of Anne vested that right in the author.

The more relevant point for our discussion is how easy it became to copy things.

When I was a lad it was common to buy an album and copy it to a cassette tape. Sometimes we’d make copies for friends. That was a violation of the music company’s copyright, but we didn’t care, and nobody enforced it.

Copyright Anarchists

With every increase in technology it gets easier to produce content – and to make copies – and this has contributed to the idea of universally accessible information.

In the early days of the Internet, a lot of people saw that dream coming true. The Internet could give everyone in the world access to all the world’s information. A substantial subset of the technically inclined people and businesses promoted an attitude that information should be free and freely accessible.

Napster was a good example. They created a file-sharing site that took what I was doing as a kid – making copies of albums on cassettes – and shot it to the moon. Everyone who joined Napster had access to everyone else’s digital music library. It was a clear copyright violation and put a big dent in music sales.

Eventually they were shut down, but Napster was emblematic of the problem – the clash between free access to content and copyright.

A friend was a big fan of Napster and I challenged her on the ethics of taking copyrighted content like that. (By this time in my life I had given up on my former thieving ways and believed in copyright.) She said that taking a physical object is stealing, because it robs the owner of the object. But copying a digital object doesn’t harm the owner in any way. He keeps what he had.

When I asked about the harm done to the musicians and music companies, she said they were greedy bastards and deserved it anyway.

Google is the ultimate corporate expression of this “information wants to be free” attitude. Their mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” That means free, which they’ve confirmed multiple times in their annual reports and other public statements.

Google wants free content supported by ads that they control.

Who Benefits from Copyright?

We’re going to see a pattern here, which is that Big Tech efforts to do what they want with content actually undermine what they’re trying to do.

Copyright is an important legal concept that protects individual creators and corporations, and helps society as a whole.

It helps individual creators by giving them the right to determine how their content will be used. If there were no such protection, creators would have very little incentive to make anything because big companies would just take it and use their greater resources to outcompete the creator.

It helps companies in a similar way. When a company buys the rights to some content, they don’t want their competitors stealing their ideas.

It helps society by providing an engine for creativity, new ideas, and advances – in technology, in art, in science, and in many other ways.

Exceptions to Copyright

Copyright isn’t absolute. We grant exceptions for fair use, where an author can use a small portion of somebody else’s copyrighted material – without their consent – provided they give credit to the original creator.

There are special provisions in copyright law that allow libraries to do things that would otherwise infringe on copyright. The goal is to balance the interests of copyright holders and the general public.

Lending a book is not considered a copyright violation due to things such as the first-sale doctrine, which also allows a book owner to give away or sell a book.

These legal principles were all established before the advent of digital content, and some of them don’t apply very well. For example, lending a digital book is a very different thing than lending a physical book.

AI and Copyright

The way a computer processes information is very different from the way a human does. For example, when a computer plays chess, it compares the configuration of the board to a database of millions of chess games. It makes its move based on which move from that configuration ended up winning. I’m no expert on chess, but that’s very different from the way a human plays the game.

The way a computer processes information is very different from the way a human does. For example, when a computer plays chess, it compares the configuration of the board to a database of millions of chess games. It makes its move based on which move from that configuration ended up winning. I’m no expert on chess, but that’s very different from the way a human plays the game.

In the same way, the way AI processes words is very different from the way a human does. A word like “king” is represented in an AI system by a multidimensional vector. Something like [0.2, -0.4, 0.7, …] There might be hundreds of dimensions, and the values are assigned so that words with similar meanings are located close to one another in this multi-dimensional space. Words might be close along one axis and not on another. “King” and “queen” are close in the context of being a ruler, but they’re not close in the context of sex, while “king” and “duke” are close in the context of sex, but a little farther apart in rank.

These sorts of vectors allow a computer to use math to figure out words, like king – man + woman = queen.

AI models don’t understand anything. They just have a complicated mathematical representation of words and phrases that are derived from processing huge amounts of text.

Some people claim that allowing a large language model like ChatGPT to be trained on a library of information is no different than a human going to library, reading 100 books, and writing a new book on that topic.

There are some important differences.

- A human author does not have perfect recall. A computer can.

- A human processes the information in a completely different way. In other words, all the balancing and tinkering and rules we’ve developed about libraries were constructed with humans in mind, not computers. It’s not likely they’ll all apply in the same way.

- When a human relies on a particular source extensively, he’s obligated to cite it. AI doesn’t do that. It doesn’t give any credit to the original author.

Possible solutions

In addition to thinking through all our previous assumptions about copyright in light of AI, we need to make distinctions between works in the public domain and works that are still under copyright. For example, it might be acceptable for AI to have unlimited access to works in the public domain, but would have to get permission from the copyright owner for works that are not.

The very technology that makes a large language model work could be used to create expectations about when the AI needs to give credit to the original author.

Remember those multidimensional vectors I mentioned? A similar technology could determine how similar the output of an AI system is to any given work, and different rules could be established for degrees of similarity. For example, if the output is very similar to pre-existing text, the AI might have to provide a citation, or even to pay for the use of that content.

Finally, copyright isn’t the only way to regulate access to content. There’s also something called Creative Commons, which allows copyright owners to set the terms under which their creation can be used. It has the benefit of not being tied to any one jurisdiction’s laws.

Takeaways

While this is all being worked out, publishers should strengthen their company’s position on copyright and challenge any violations. Specifically, they should change their terms and conditions to make it clear that their content may not be used to train large language models without the publisher’s explicit consent.

It would also be a good idea to brush up on creative commons licensing to see if that might be a useful tool for defining how your content could or could not be used in the future.

Part 2 – The Search Bargain

The Internet was undiscovered country for publishers. It was a new way to reach audiences and to monetize their content – mostly with ads, which were very profitable at the time.

Search became the gateway, or the discovery tool. But it didn’t start like that.

Before Good Search

If your memory stretches back as far as mine does you’ll remember that before search there were directories.

Sites were categorized at a high level – arts, science, sports, etc. – and then you could drill down to find the category you were interested in.

Content providers would submit their sites to the directory manager with a request to be included in such and so category. That’s how you got found in those days. The secret was to have lots of links to your content.

Enter Google

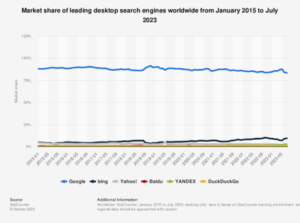

Google changed all that. While there were search engines before Google, theirs was so much better that it quickly became dominant and directories faded into irrelevance.

Search engines would crawl websites, scrape the content, index it, and then visitors would search against that index.

This was a big mistake. Publishers should have set terms for how their content could be used, but they went along with the assumption that anything out there on the internet was freely available – and in this case, free for the taking. They should have asserted their rights and demanded some visibility into the search index.

What happened instead is that they became slaves to the index and the algorithm.

Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. That means free, which they have said explicitly in many public documents.

The Google bias is towards free content supported by ads. Which they control.

Lesson 1

What we’ve seen so far exposes the fundamental conflict between the interests of Google and the interests of publishers. Publishers want to determine how and under what circumstances their content is consumed. “Free with ads” is one model, but not the only model. Also, Google operates under the assumption that if content is posted on the internet, they can take it and do what they want with it, which is clearly not in publishers’ best interests.

That underlying assumption has come home to roost with AI, as we’ll see later.

The Google Effect

Google rules search. Nobody else is even close. That means Google controls content discovery, so if you want to be found on the internet, you have to follow Google’s rules – which they change from time to time for their own reasons. Content creators have no say in the matter. Their content is being crawled, scraped, indexed and organized by Google the way Google wants.

Google rules search. Nobody else is even close. That means Google controls content discovery, so if you want to be found on the internet, you have to follow Google’s rules – which they change from time to time for their own reasons. Content creators have no say in the matter. Their content is being crawled, scraped, indexed and organized by Google the way Google wants.

This is outrageous. Why did content creators allow this to happen?

Google doesn’t only control content discovery, they also dominate the ad space – not only on their search results pages, but on most websites.

I’m not a lawyer, and I don’t know if this is technically a monopoly, but it’s certainly a case of the classroom bully eating everyone else’s lunch. And publishers just went along with it.

Google vs. Publishers

Publishers have many different choices for how to monetize their content. Google has created an environment that heavily biases things towards one model – that is, free content supported by ads controlled by Google.

This has created a perception with the public that content ought to be free. That’s the natural, expected thing. Any effort to charge for content, or to add any friction to free access to content seems … rude.

This expectation that content should be free lowers the perceived value of content.

We’re all familiar with this bias. If something costs more, we typically assume it’s better quality and has more value. That’s not necessarily true, but it’s how we think.

When I was at Kiplinger I took over management of a product called the Family Records Organizer. It was a solid product, but sales were slipping. I raised the price and sales went up.

By creating the assumption that content should be free, the Google-driven internet has devalued all content.

The funny thing is that Google needs this content – which they don’t create. Publishers have always had leverage here, but they’re never used it. They’ve allowed to write the rules of the game.

Where “free + ads” fails

“Free supported by ads” is a perfectly legitimate way to monetize content. The important point here is that it’s not the only way, but we’ve allowed it to become the default assumption.

That model doesn’t work as well for some specialty content because advertising tends towards the general and the popular. It’s harder – not impossible, but harder – to support specialty content with that model.

Ads are also extremely disruptive of the reading experience, especially on mobile sites. Some mobile sites are virtually unreadable because of the ads.

The Whole Industry is Infected

As the gatekeeper of discovery and the dominant player in the ad space, Google’s perspective wins. It’s not just their doing. As I said in Part 1, most of Big Tech believes in this idea of free content supported by ads, and that’s infected all content delivery platforms.

Consider podcasts. The default assumption is that you get the podcast for free. It’s very difficult to integrate podcasts into a membership or subscription model. Some people have done it, but there’s a lot of friction involved. You have to fight against the assumption of the Google model.

Even where it is possible to put a podcast behind some sort of membership wall, it’s often not the podcast producer who gets the customer information. This is another way Big Tech has been eating publishers’ lunches. The model is that your customers become their customers.

The Top of Your Funnel is All Wrong

My friend Chris Moffa says there’s all the difference in the world between someone who will pay you a dollar and someone who won’t.

Subscribers and non-subscribers are different in many ways. Subscribers tend to be older and more educated, they have more money, and they subscribe to multiple different services.

Those aren’t the people you’re attracting on the “free supported by ads” internet who discover you through Google. You’re attracting people who think asking for payment is rude.

Unfortunately, that horse is out of the barn, at least for the time being. As it stands right now, most people assume the “free content” attitude. But it would be interesting to break out of the mold and consider other ways to get the right kind of people – that is, people who are willing to pay for content – into the top of your funnel.

That’s probably not through Google search.

People Became the Product

I’m not going to spend much time on this because it’s slightly off my topic, but The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff explains the next step in Google’s dominance. It’s a hard book to read, but Ms. Zuboff has a lot of YouTube videos that give a nice overview.

The idea is that Google discovered a new resource – personal information. They can package up “user” activities to create audiences for advertisers, and they can find ways to nudge us towards certain behaviors.

It’s funny / not funny that we’re called “users,” which is what a lot of addicts are called.

The bottom line is that Google and other Big Tech companies have a set of interests that do not align with the interests of publishers and content creators.

Part 3 – Generative AI

This is the big issue for publishers. Is generative AI a useful new tool, or an industry-destroying calamity?

Answers, Not Homework

A popular search on Google is “how old is [some celebrity].” Also, “how tall is,” “who is so and so married to,” and so on.

Some enterprising people built database-driven websites around these questions. They wanted to get that traffic and get their penny of advertising revenue. It was a very smart model.

But now, if you type “how old is Michelle Obama,” Google doesn’t send you to one of those websites. It just gives you the answer. In that narrow way, Google is no longer a discovery tool, it’s an answer engine.

Wikipedia is facing the same problem. Wikipedia has had a long run as the top search result on many queries. If you searched on the Battle of Trafalgar, Wikipedia was the top result. It still is. But now, next to the list of webpages, Google provides a quick summary from Wikipedia. That summary might be enough to answer your question, so Wikipedia loses the page view. There’s no need to click through.

I’m a fan of Star Trek, and I like science fiction movies. I’ve never seen a version of the future where someone asks the computer a question, and it replies with a list of articles to read.

No. It answers the question.

AI has made that possible. ChatGPT doesn’t give you homework, it gives you an answer.

In that world, how can publishers monetize their content? People won’t be clicking through to your webpage. They’ll get their answer from AI, which might have stolen the answer from your content!

I Am Altering The Deal …

You may remember that Lando Calrissian made a bargain with Darth Vader, but Vader simply did what he wanted to do because nobody could stop him. “I am altering the deal,” he said. “Pray I don’t alter it further.”

You may remember that Lando Calrissian made a bargain with Darth Vader, but Vader simply did what he wanted to do because nobody could stop him. “I am altering the deal,” he said. “Pray I don’t alter it further.”

I find it amusing that Darth Vader is the only character in Star Wars who encourages us to pray.

The point here is that there was a deal. Crawling, scraping, and indexing your content was accepted by publishers because it fed an algorithm that provided discovery for your website.

Darth Vader – by which I mean Google and all the AI monsters out there – have altered the deal. Now they slurp up your content to replace you.

The Old Deal is Over

I would like to believe that publishers had a grand, long-term strategy for how they were going to make this internet thing work. The reality is that they just capitulated to Big Tech and grabbed what scraps they could along the way.

If there was anything like a strategy, it was something like “okay, we’ll put our content out there for free, and we’ll follow all the crazy SEO rules, but we’ll set the terms for use once you get to our site.”

We’ll show ads. We’ll bug you to sign up for our e-newsletter. We’ll ask you to register or subscribe. And so on. But it was all premised on discovery and traffic from search.

AI has ripped that deal to shreds. They steal your content and answer the questions that your readers are asking. You’re not necessary any more.

Expect a Decline in Site Traffic

Why go to a website and read an article to find an answer to your question when AI will just give you the answer?

The strategy that publishers adopted in the era of Google-dominated search won’t work in the developing era of AI-generated answers. Just as Google undermined the business model of sites that gave details on celebrities (“How tall is Tom Hanks”), generative AI is going to undermine search, which will reduce traffic to your site.

Reconsider Bots and Crawling

In the old model, if you wanted your content found you had to allow the search engines to crawl, scrape, and index your content. But now those very same bots are feeding your competition, which is generative AI. Why let them do that? Why not cut off the bots?

That’s a difficult question. If your revenue model depends on search traffic, you want these search crawlers to index your content, but that’s also feeding the generative AI that is working to undermine you.

The smart thing to do right now is to change your terms and conditions to explicitly forbid anyone to use your content to train AI. I doubt the copyright thieves in Big Tech will honor that, but at least you’ve put a stake in the ground, and it might provide some help later – when all this mess goes to court.

A Threat to Google?

I’ve mentioned that the era of search is coming to an end. When it’s a choice between a tool that will answer your question and a tool that gives you additional work to do, the former will win. That is, people will migrate away from search and towards chat bots.

Google’s chatbot recently had an amusing public relations disaster, but that’s not the real threat. I’m wondering if Google is so tied to its ad business that it won’t be able to compete with other LLMs that can start fresh. We’ll see.

Personally, I have a love-hate relationship with Google. I love their services. I hate their arrogance.

Takeaways

Right this second, AI bots are scraping your content, that you paid to create, using your content to train their large language models, and creating products to compete against you. Are you going to allow them to continue to do that?

The nuclear option is to amend your robots.txt file and block them on the back end, at the server level. But that also means killing your own search traffic.

What you should certainly do is amend your terms and conditions to say that your content may not be used to train AI without your explicit consent.

At the same time, you should create your own LLM on your area of specialty, and you should work to characterize the general LLMs as unreliable and biased.

To the extent you can, you should work to promote appropriate rules for how LLMs use copyrighted material, and you should look into Creative Commons licensing.

Finally, break free of the “free supported by ads” mindset. It might still be the correct model for some publishers in some markets, but don’t allow it to reign in your thoughts as the default. Start thinking about other ways to monetize your content.

Generative AI is a huge threat to publishers. We’re very late to the game in thinking all this through, but better late than never. In the final section I’ll talk about what’s next.

Part 4: What Comes Next?

Openness vs. Carefulness

Human society needs to have two different attitudes towards change. We need the spirit of exploration and discovery so we can find new things and grow, and we need to be cautious, because some new things kill you. If you look at most new technologies, they offer great hope and promise but at the same time might cause concern.

Human society needs to have two different attitudes towards change. We need the spirit of exploration and discovery so we can find new things and grow, and we need to be cautious, because some new things kill you. If you look at most new technologies, they offer great hope and promise but at the same time might cause concern.

For example, back when they figured out now to fill cavities, that was better than having a tooth pulled, but at the same time you’re introducing this crazy new substance into your body, and they weren’t exactly sure that was a good idea. In some cases a new technology solves one problem and causes others.

Take plastics as an example. Plastics are fantastic and solve innumerable problems, but now they’re in the oceans and in our bloodstream and so on.

We have both attitudes right now with AI. Some people believe it’s a wonderful thing that’s going to tremendously increase human productivity and maybe usher in an era of peace and prosperity. Other people are afraid that it’s going to take over and destroy us.

Both points of view are necessary.

The Era of Search is Fading

There was a time when “the internet” mostly meant web pages, and search was the front door. That was never completely true. America Online was a popular walled garden that had a life of its own.

There was a time when “the internet” mostly meant web pages, and search was the front door. That was never completely true. America Online was a popular walled garden that had a life of its own.

Over time, search as a discovery tool for web pages has been displaced to some extent by other tools – apps, email, social media and such. A surprising number of people use TikTok as their front door to everything on the Internet.

In addition to all this, answerbots like ChatGPT will cut into search’s share of our eyeballs. As I mentioned earlier, why settle for a list of potentially valuable links when you can just get an answer?

Find Other Ways to be Discovered

Building a web page and creating a great search engine program won’t cut it anymore as a strategy to reach your market. People are all over the place online, and traditional search isn’t the only way they look for things. Focus your attention on where your market spends their time.

This might require you to change your format or your style. If your market doesn’t want to read, quit pushing long articles on them. Make videos and podcasts. Use cartoons if you have to.

AI might help here. Create excellent content the way you normally do, and use AI to transform it into 35 other formats.

The image here is from a proverb in a children’s book. “He who has a thing to sell and goes and whispers in a well is not as sure to get the dollar as he who stands up high and hollers.”

Start Selling Answers

There are still problems with generative AI. It still makes stupid mistakes, and you can’t trust it yet. But the concept of getting an answer to a specific question is the way to go. I don’t want to have to read a long article on Roth vs. traditional IRAs. I want the right answer for my situation.

Publishers should start building their own large language models in their specific niche.

How do you make money on this?

There’s the tried and true – ads, registration, and subscriptions. You can do an upsell from a simple question to another product, or a consultation. You can license your carefully curated answer in your area of expertise to one of the larger LLMs.

You Can’t Stop Progress

Hating on AI won’t stop it, but that doesn’t mean you have to keep feeding it. Find ways to use it, but also find ways to get leverage over it.

Will AI Train on AI-generated BS?

I’ve spoken about the very real and very serious conflict between Google, AI, and publishers. Big Tech is stealing your content without your consent so they can use it to replace you.

But AI has a weakness. It needs fresh material.

If, as some people say, AI is going to flood the internet with a tsunami of bullshit, what content will the LLMs train on? Will they start feeding on their own BS?

If AI destroys publishers, are they salting their own fields? What will they train on? TikTok videos?

This is an opportunity for publishers.

What To Do Now

- Stop feeding the beast for free. Let’s see if we can starve it of decent content and get back into a position where we have some leverage.

- Use AI to transform your content into as many different formats as you can.

- Break out of the “free supported by ads” mindset.

- Create your own LLM and think about creative ways to monetize answers.