When marketers get too caught up in chasing the “golden record” in a Customer Data Platform, they can allow “identity” to foul up their use cases.

My daughter Anne had an experience that illustrates this well. We planned a family trip, and I added her personal email address as a guest on the reservation. But she received a reminder about the trip from the travel company on her work email, which made her nervous. Why did they send the reminder to her work email? Who told them about her work email?

My daughter Anne had an experience that illustrates this well. We planned a family trip, and I added her personal email address as a guest on the reservation. But she received a reminder about the trip from the travel company on her work email, which made her nervous. Why did they send the reminder to her work email? Who told them about her work email?

Near as I can tell, this is what happened. Anne had created an account with the travel company using her work email for a work-related event. Somewhere along the way, the travel company added her personal email to that profile. When I added her personal email to the guest list, the travel company attached that action to her profile, so when it came time to send out a reminder, it used the default email in that profile, which was her work address.

In other words, in an over-zealous attempt to create a “golden record” for Anne, they forgot the purpose of the use case, which is to send a reminder to the guest email that’s entered for the event.

The lesson is that there are times when stitching together all of a customer’s information into a single profile can accidentally interfere with your use cases.

Take another example. Joe is a good customer. He’s an office manager, and he buys things from your store for his company. But he has a side hustle and buys a lot of the same things for his personal use. He keeps those accounts separate, using separate email addresses.

Merging those records together doesn’t help your relationship with Joe. In fact, it annoys the heck out of him, and gets him in trouble with accounting.

And then there’s my experience. I work as a consultant for many different companies, and sometimes I need to have accounts on the same service for different clients, on different email addresses. Some of these services won’t allow a customer to have multiple accounts with the same phone number for 2-factor authentication. So I have to find a workaround that doesn’t help me or the service provider.

These are all examples where merging records around a person can ruin a customer experience. But there are counter-examples as well – where you’d better merge the records.

If you’re a restaurant that delivers food, and you know that Sam has an allergy, you need to make sure that information migrates across all of Sam’s accounts.

The bottom line is clear: use cases are more important than identity. But how do you know when and what to merge?

I’ve created two frameworks to work through these issues: the device framework and the person framework. By thinking through each use case with both frameworks, you can develop the correct procedures for merging records.

|

Device Framework |

Person Framework |

|

|

Devices

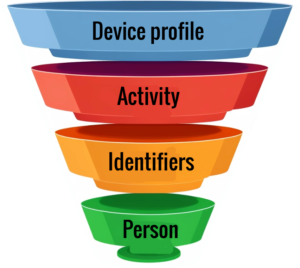

The device framework is the way most people work through their customer data issues.

Device profile: A device makes a request to your site. Your CDP creates a profile for that device and collects information about it. At this level, you can segment on things like operating system, geography, screen size, etc.

Activity: If that device makes more than one request, you can start to enrich the profile with other information, such as what kind of content is accessed. With this activity information, you can segment on things like “likes videos,” or “accesses tax content.”

Identifiers: Some of the device’s activities help to narrow down who is behind that device. For example, a device might make a request to your site after clicking on one of your emails. That helps to create narrower segments, and in some cases helps you to identify the person.

Identifiers can be used to create very powerful segments, like “everyone who is registered for our e-newsletter.”

Person: Some identifiers make a strong connection to a person, while others only hint at the person’s identity. As you collect identifiers, you can sometimes resolve the profile down a particular person – with more or less certainty, depending on the nature of the identifiers you have collected.

Once you have a profile identified with a person, you can develop use cases such as presenting renewal offers near expiration.

People

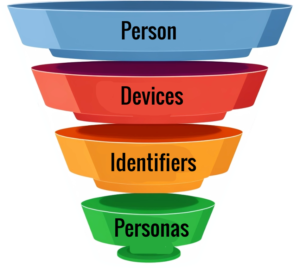

The person framework is what helps you avoid the problems mentioned above, like Anne’s concern about the misuse of her work email, or my troubles with 2-factor authentication. This framework requires us to step out of a data-centered world and think about the real lives of actual people.

Person: Rather than starting with a device profile and trying to resolve it down to a person, we start with a person and imagine how that person behaves in the real world.

Let’s go back to Joe, your good customer who purchases office equipment for work and for his home business.

Devices: Joe has two phones: one from the office, and one for his personal use. He’s careful to do office work on one, and home / personal work on the other.

Joe also has an office PC, but a Mac at home. Again, he uses one for office work, and the other for his own ventures.

Identifiers: Joe is very careful to keep things separate. His office email is for office work, his personal email is for friends and family, and he has another email address for his side hustle. Joe does not want these merged or confused.

Personas: Rather than thinking of Joe as a single person, you have to think of Joe’s three distinct personas: Office Joe, Personal Joe, and Side Hustle Joe.

Using these frameworks for your use cases

Now that we have the basics, let’s take one use case and work it through both frameworks. The use case is this: “Send relevant job listings to all mechanical engineers who opt into our job postings email.”

Device framework

The top of the device funnel doesn’t help much with this use case, because we can’t identify mechanical engineers by what kind of device they use. Once we get to the activity level, we can find profiles that frequent content relevant to mechanical engineers, and we can use on-site quizzes or simple questionnaires to gather identifiers. In this case, job title.

Once we have the job title, we can create a segment of mechanical engineers and promote the “sign up for job listings for mechanical engineers” email list.

That’s good enough for this use case. We don’t need to resolve identity down to the person, although a name might be good for personalizing the emails. In fact, resolving things down to the person might create a problem, as we’ll see.

Person framework

Julia, our mechanical engineer, works for a company that doesn’t take kindly to people looking around for new gigs, and the IT department keeps an eye on all the emails that come to office addresses. Because of this, Julia is very careful to keep her work and personal lives separate. While she only has one laptop, she does all her office work in Chrome, and all her personal browsing (from home) in Firefox. She signs up for the job-posts email on her personal account, but not on her work account.

If an overzealous data scientist merged these two accounts into one profile for Julia, and started sending the job-post emails to Julia’s work address, Julia would not be happy.

Conclusion

People are more complicated than your data structure recognizes, so it’s important to view your use cases from two perspectives: from the data side (the device framework), and by imagining the life experiences and concerns of real people, who often act online through different personas.

Make sure you structure your data, your merge rules, and your use cases, to allow people to act within whatever personas suit them, and don’t try too hard to create a single profile for each person in every case.